It’s about time this Shrimp ‘n’ Grits recipe was added. We automatically make it over, and over, and over. Rinse-repeat, and repeat. It’s both a requested family favorite and one of those last minute “oh, we’ll do this tonight” when all other dinner options are exhausted and abandoned. Shrimp ‘n’ Grits is an indulgent recipe from the coastal Carolina Lowcountry. Almost every dining establishment in this area has their own house special version with proprietary flare.

Charleston, South Carolina is where S ‘n’ G is believed to have originated as a breakfast dish. It’s also where we first enjoyed it way back in 2004. I can’t recall the exact recipe, but it was simply scrumptious–creamy tender grits, seasoned shrimp, a bit of bacon, and green onion. Since then, The Hubby has perfected our house special recipe.

The Lowcountry is a unique tidewater area where cultures combined over the centuries–Native Americans, Enslaved Africans, and European Colonists. Charleston was officially founded in 1670 as Charles Town, after English King Charles I. Over the decades, Charles Town morphed into a colonial capitol, major shipping and naval port, and a wealthy city of firsts–public college, playhouse, golf club, shots fired in the U.S. Civil War, and a successful combat submarine.

In April 12, 1861, the first shots of the U.S. Civil War took place in Charleston. South Carolina was the first of the Confederate States to secede from the Union. The only fort the Confederate Army was unable to seize was Fort Sumter, located at the mouth of Charleston Harbor. Cadets from The Citadel, a military Confederate college in Charleston, are believed to have started the bombardment against troops stationed at Fort Sumter. (The Hubby attended The Citadel for a hot minute too! His tar bucket and plume hat is in my MIL’s attic.)

A week later, President Lincoln issued a blockade on all southern ports. The goal was to prevent any and all supplies from going into the Confederate States of America. This blockade is known to history as “Scott’s Great Snake,” named after Union General Winfield Scott’s plan. Affecting 12 major ports along 3,500 miles of waterways, the Confederate States were desperate.

Three innovative engineers in New Orleans devised a way to eliminate the Union Navy warships positioned in southern harbors. James McClintock, Baxter Watson, and Horace L. Hunley put their design skills to work and started building the first prototypes of hand-cranked submersibles. Their first model was Pioneer in February 1862. With a crew of three men, the 30-foot long, 4-foot diameter Pioneer was never put into service. Although it tested well in Lake Pontchartrain, Pioneer was scuttled by the Confederates as the Union Army invaded New Orleans. McClintock, Watson and Hunley moved their operation to Mobile, Alabama and tried again.

Learning from the failures and successes of Pioneer, the engineering trio teamed up with the talents of Thomas Park and Thomas Lyons of Park & Lyons Machine Shop on their second attempt…American Diver. At 36-feet long, 3-feet wide, and 4-feet, American Diver was tapered at the ends like a knife blade. The men tried to use a steam-powered engine to propel the sub, but the engine never created enough power to move it. A hand-crank system was installed. Just when American Diver began ship attack trials in February 1863, it sunk being towed in Mobile Bay during a storm. The sub was never recovered, and luckily no lives were lost.

Going back to the drawing board, the men built their 3rd and final sub commonly called the “Fish Boat.” Ultimately it is named for H.L. Hunley. Now 40-feet long and 4-feet 3-inches in diameter, the Hunley submerged and passed completely beneath a floating barge or warship. Satisfying its harbor trials in August 1863, the sub was hauled from Mobile to Charleston by railroad car and into service under the Confederate Navy. However, while moored at Fort Johnson, the sub unexpectedly sank. Maybe it was due to a passing ship causing water to flood open hatches, or mooring lines from another ship rolling the sub over. No one determined the cause, but 6 of the 8 men onboard drown. Weeks later, the men and the sub were recovered. H.L. Hunley demanded the sub be given back to him to command, and a second crew was called up.

In October 1863, Hunley and his new crew of 7 men scheduled a demonstration to show how the Hunley could submerge below and beneath the ship CSS Indian Chief. The Hunley descended into Charleston Harbor and wasn’t seen again. For a month, rescuers looked for the sub and eventually found its bow sunk into the mud. Its stern was floating upwards, making it easier to locate and hoist up. Hunley’s second crew of sailors perished. Rescuers believed the forward ballast tank was left open, filled with water, and sunk almost immediately.

The Union Navy, specifically Rear Admiral John Dahlgren, learned of the Hunley’s mission and demise. He ordered his fleet to implement anti-submarine warfare tactics, including chains hanging down into shallower waters and watch standers trained to look specifically at the water’s surface patterns. H.L. Hunley, the ship’s main financial backer, was now gone. Lieutenant George E. Dixon and William Alexander stepped up to assist, truly believing the Hunley could be instrumental in breaking through the blockade. The design of the sub was modified yet again, but now with a spar containing a torpedo and fashioned to the submersible’s bow. General P.G.T. Beauregard, the C.S.A. Navy’s skeptical commander, reluctantly gave permission for Dixon and his seven-man crew of now-volunteers to train. The sub wasn’t allowed to dive beneath ships, as attempted two times before, but could operate almost entirely at the surface, and with the sole purpose of ramming its torpedo into a ship’s hull below the water line.

In February 1864, under calm night seas, Dixon and his men set their sights on the USS Housatonic. Thinking a porpoise was heading towards them, lookouts on the Housatonic didn’t realize it was too late until it was. The torpedo exploded in the hull, causing the ship to sink within 5 minutes in Charleston Harbor. Of the 155 crew, 5 of the Housatonic’s crew died. About an hour later, a blue light was seen at the mouth of Charleston Harbor. Dixon was expected to signal the Hunley’s success and return with this color, but unfortunately the sub was never seen…until 131 years later.

Searchers believed the Hunley sank near the Housatonic, but this wasn’t so. After 15 years of looking, the National Underwater and Marine Agency discovered the Hunley off the coast near Sullivan Island in about 30 feet of water, and under two feet of sediment. Bringing the Hunley to the surface was a multi-year long endeavor. You can read about the specifics here. In August 2000, the Hunley was raised to the surface after 139 years on the bottom of the harbor. It was immediately placed into a gigantic 75,000 gallon tank filled with fresh water to preserve it and its contents at the Warren Lasch Conservation Center, where it remains today. In 2004, we visited Charleston and the Hunley. The Hunley itself was not clearly visible in that tank, and my pictures from then are lost.

Today, the Hunley is preserved in a tank of water and sodium hydroxide. Visitors to the Warren Lasch Conservation Center learn about the possible reasons for why Hunley sunk, and sit in the same movie props from the 1995 film called The Hunley. Son B wasn’t a year old during this visit, so his experience in 2004 entailed the uncomfortable, collapsible stroller we used. In 2024, at 6-footish, he experienced the same movie prop Son A did. Clearly, Son B thought this volunteer assignment would’ve been cramped, cold, and dark. Miserable to say the least, but honorable given the scope of what the crew was trying to achieve.

Hunley’s third 8-man crew was officially identified and laid to rest in 2004 in Magnolia Cemetery. The first and second ill-fated Hunley crews, including engineer and namesake H.L. Hunley, are also interred in the same area plot.

When archeologists and forensic scientists tried to determine who was sitting where on the Hunley when it sank, they examined several things. Physical remains like skeletons were obviously the first. General body structure, height, weight and ethnicity were compared to the muster roll of the 8 men who volunteered. However, no photographs exist of any man onboard. This led to forensic artists reconstructing the overall appearance of each man based on casts of their skulls.

Lt. George E. Dixon (sitting far left in the photo above) was in command of the Hunley. He wore several personal items clearly identifying him. One of these was a $20 gold coin given to him by a young lady when he left his hometown of Mobile, Alabama to fight for the Confederacy in 1861. A year later, during the Battle of Shiloh in 1862, Dixon was shot. The bullet struck the gold coin, absorbing the impact, and saved his life. The gold coin has the following words inscribed on it:

Shiloh

April 6, 1862

My Life Preserver

G.E.D.

Another sailor had some confusion surrounding his name. Simpkins? Lumpkin? Cinncinatus Lumpkin! Originally thought to be Simpkins, based on the handwritten records of the day, his effigy was listed as such in 2004. But when researchers at the Warren Lasch Conservation Center began digging in, they saw the mistake they had made and corrected this moving forward, including the grave marker at Magnolia Cemetery. The display in the Center’s museum still notes the misconception. Pillows bearing the Confederate States of America Medal of Honor display were created before this was clearly identified.

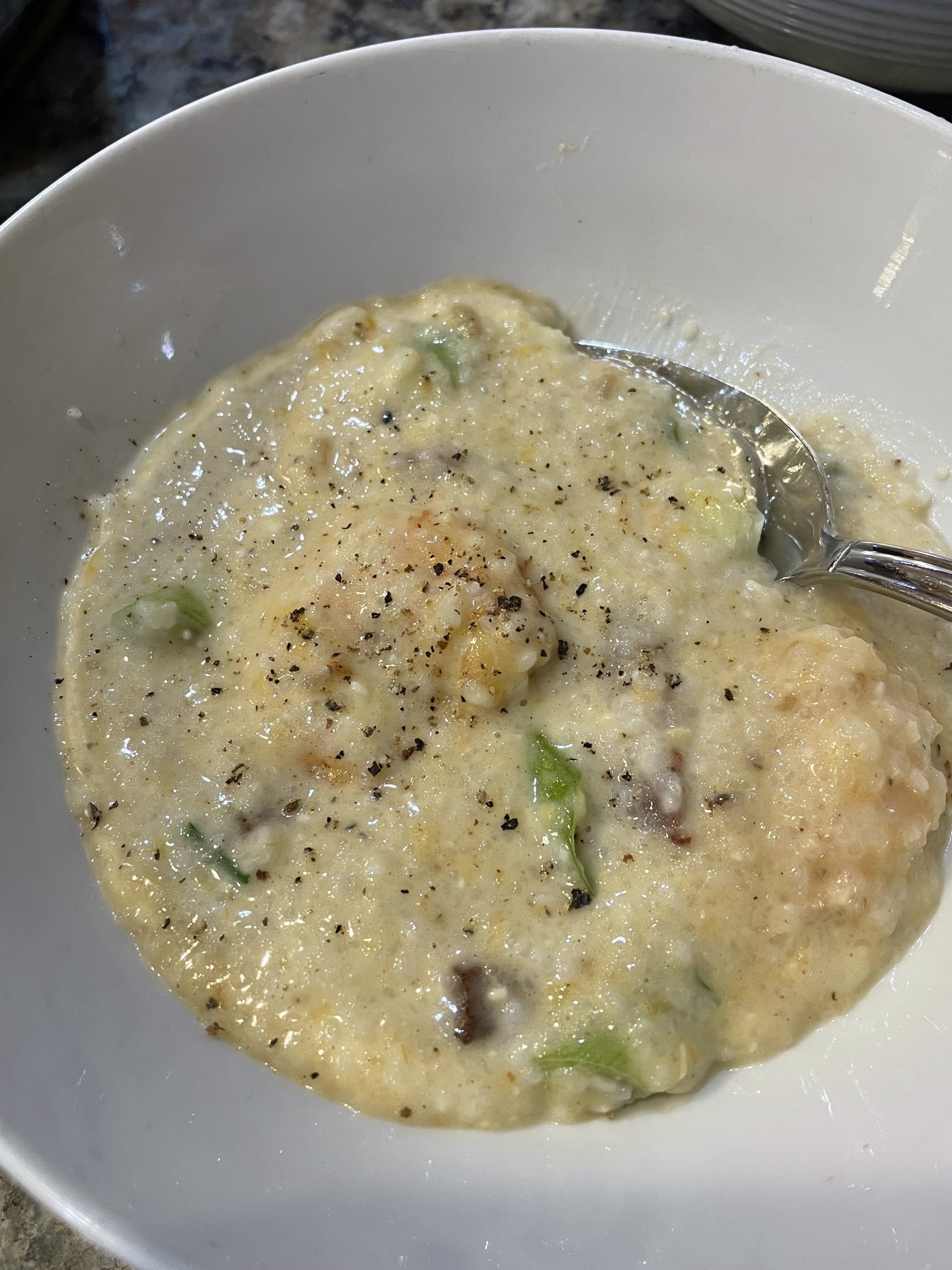

In honor of the 21 sailors lost onboard the Hunley, and in conjunction with a lasting recipe standing our kitchen test of time, I present The Hubby’s Shrimp ‘n’ Grits. To begin, start with the grits. You can opt for quick-cooking or instant grits, but a stone-ground version will give you a heartier mouthfeel. Cook them according to the package directions, but be sure to add heavy cream to the cooked grits for a creamy consistency.

The shrimp component to this dish is the easiest by far. Cook bacon lardons (1/4-inch wide slices) until crispy. Remove the bacon, but leave about 3 tablespoons of fat in the pan. Add the shrimp and garlic, cooking until fragrant and pink. Bourbon is the key with The Hubby’s recipe. He doesn’t use a high-dollar bottle, but one that you’d use to make bourbon and cokes. Deglaze the pan and remove from the heat. To the grits, stir in shredded Mexican cheese blend. We’ve tried flavor specific shredded cheese, but find this blend to be both tangy and mild.

You can stir the shrimp mixture and green onions into the cheesed grits, or put on top of them in a bowl. Either is delightful and southernly scrumptious! Enjoy!

PrintShrimp ‘n’ Grits

According to The Hubby (and My MIL and Aunt D.), Shrimp ‘n’ Grits is one of those recipes that sounds harder to make than it is. His recipe combines creamy cheesy grits with bourbon-garlic sautéed shrimp, enhanced with diced bacon and green onions. Heaven in a bowl!

- Author: The Hubby

Ingredients

For Grits:*

1 c. stone-ground grits

3/4 c. water

1 tsp. salt (table, kosher or sea)

1/2 c. heavy cream

For Shrimp:

1/4 lb. diced bacon (about 1 to 1–1/2 cup)

1 lb. shrimp (medium to large sized), peeled and deveined

4–6 cloves garlic, finely diced

1/3 c. bourbon

Salt and pepper to taste

2–1/2 to 3 c. shredded Mexican cheese blend

1/2 c. green onion, cut on bias in about 1/4-inch pieces

Instructions

(*Cook grits according to package directions.) If using stone ground grits, bring water and salt to a boil over medium-high heat. Whisk in grits. Lower temperature to a simmer and cook until grits are tender and water is almost absorbed (about 30-45 minutes). Cooked grits should be a texture like thickened oatmeal. Stir in heavy cream and set aside on a warm burner.

Cook diced bacon in a skillet over medium heat until browned. Remove bacon to a paper-towel lined plate to drain, but leave about 3 Tbsp. of bacon grease in pan. Add shrimp and diced garlic. Turn shrimp until they become pink. Stir in bourbon.

Remove cooked grits from stovetop. Stir in shredded cheese, bacon, green onion and bourbon shrimp. Season with salt and pepper, to taste. Serve immediately with additional green onion or hot sauce, if desired.

Notes

*Cook grits according to package directions.