As promised, we’re in the Bluegrass state (aka Kentucky) today. If you read the title (which I’m sure you did), that “slang-whanging stump speaker” is none other than our 16th U.S. President Abraham Lincoln. President Lincoln (R-IL) acquired this zinger from one of his 1860 presidential opponents. Whether it was said by John Bell (Constitutional Union-TN), John Breckinridge (Southern Democrat-KY), or Stephen Douglas (Northern Democrat-IL), I am unsure. Irregardless, it was meant to embarrass him for his limited statesman experience and perceived small intelligence. Lincoln, obviously, won the 1860 election and the rest is history.

And there’s a lot of history books written about Abraham Lincoln! In the Ford’s Theater Center for Education and Leadership in Washington, D.C., a tower of roughly 7,000 Lincoln books stands 34 feet tall and 8 feet around. As of 2012, an estimated 15,000 total books were penned about Old Abe.

When Lincoln’s name is mentioned what pops in your mind? A stovepipe hat and chinstrap beard? The Emancipation Proclamation freeing the African-American slaves during the U.S. Civil War? His 2-minute long Gettysburg Address from our Day 3 stop? The Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C.? A comedy called Our American Cousin at Ford’s Theater that clearly didn’t end in laughter? Lincoln’s iconic profile immortalized on a penny? The list could go on and on.

Ford’s Theater

Presidential Box

John Wilkes Booth’s .44 Caliber Derringer Pistol

The Petersen House

Blood Stains from Lincoln’s Pillow

The Bed Lincoln Died In

Lincoln’s life seems like a series of memorized dates or snippets we average Americans regurgitate…the 1858 Lincoln-Douglas debates, Lincoln’s 1860 election, a tumultuous presidency during the Civil War (April 1861- May 1865), the ill-fated assassination by disgruntled actor John Wilkes Booth, and Lincoln’s death on April 15, 1865. This memorized list was pretty much all I knew before a family visit years ago to the Lincoln Birthplace National Historic Park in Kentucky.

Upon arrival, this first Lincoln Memorial appeared out of nowhere. A grandiose monument out in the middle of the Kentucky rolling hills we clearly weren’t expecting. At best, we thought we’d see a well-worn frontier home with a sign proclaiming “on this site so and so was born in 1809.” After climbing 56 steps (one for each year of Lincoln’s life) into the pink marble and granite temple, we were in for another surprise. A mud-chinked cabin that honestly appeared to be out of place.

(Photo Credit: Historic American Buildings Survey, Creator, and Abraham Lincoln, photographer by Jones, Lester. Library of Congress.)

President Lincoln’s modest, poor upbringing in Kentucky and Indiana is a quick footnote. Illinois, where he became a lawyer, politician and future president, is generally where the Waze history app starts from. But still, how did this plain one-room log cabin find itself cocooned inside a grand shrine on the top of a hill?

In the early 1800’s, Lincoln’s father Thomas was a homesteader and carpenter on this 300-acre farm. The farm land was chosen, and named after Sinking Spring, which bubbled below the one-room cabin on the hill. The spring is a part of the region’s karst topography, where bedrock dissolves away creating pockets for spring and rainwater to gather in–an important feature for settlers.

Pathway to Sinking Spring

Karst-topography Sinking Spring

Around 1811, Thomas Lincoln, however, couldn’t pay for his Sinking Spring claim. When Abe was about 2-1/2 years old, the family ten miles away to 30 acres on the Knob Creek Farm. Young Abe lived here until he was around 8-years-old with his mom, Pop and sister Sarah. In this cabin, Abe watched his mother read from The Bible and experienced the death of a baby brother. He also attended a subscription school for a few months each year, well before Kentucky received free school in the 1830’s. Just beyond the field (pictured below) lies Knob Creek, where Lincoln fished, fetched water from, and almost drown in! (1). In 1816, the Lincoln family moved to a farm near Little Pigeon Creek, Indiana where Young Abe lived until 1830 and eventually moved on to Illinois.

After Thomas Lincoln and the family vacated for Knob Creek and beyond, Sinking Springs went through a series of land acquisitions. The cabin, once perched atop the knoll, also went through its own series of retrievals, revivals and sketchy backwood’s deals.

Starting with Lincoln’s 1860 election, anything and everything related to the Honest Abe was suddenly of public interest and high value. This included his birthplace cabin and site. Enthusiasm exploded after Lincoln’s untimely 1865 death. A few months after his death, a reporter visited the Sinking Springs site and noted:

However, the mysterious birthplace cabin began to appear like a mirage through a series of so-called owners. Enamored with both President Lincoln and padding his pocketbook, Reverend James W. Bigham and his son Harvey acquired the former Lincoln property. Bigham purchased a cabin for $200 in 1895 from John A. Davenport. Davenport previously moved a cabin off the Sinking Springs property a mile or so north.

Rev. Bigham’s and his son’s head swirled with grand illusions (and dollar signs) of enamored Lincoln admirers flocking to see The Great Emancipator’s birth site. Visiting the birth site seemed like a perfect side trip for the Union veterans at an 1895 reunion in nearby Louisville. The cabin purchased from Davenport was hastily put into place and an alleged relative of Former First Lady Lincoln was brought in to give presentations. Rev. Bigham arranged a tour-package deal with the Illinois Central Railroad. Visitors would pay the cost of the railroad ticket, plus a fifty-cent admission, to see the cabin and site. Rev. Bigham and Harvey sat back and waited for the crowds to swarm. This never happened. The combined cost was more than what the Vet’s Committee was willing to pay. Rev. Bigham’s poor marketing skills and exorbitant admissions fees proved an ultimate bust.

At some point, reality evolves into rumor, then myth, and finally legend. One person tells another person, who passes the story on with glorified and sensationalized details. This was the case of the Lincoln Birthplace cabin. In reality, the actual birthplace cabin was dismantled over the years for its timber to rebuild other structures.

However, shysters continued to promote and profit off the romanticism of the Lincoln Birthplace cabin. In 1894, Rev. Bigham sold the former Lincoln property to New York restaurateur Alfred W. Dennett. Dennett set another cabin on the property. He claimed this resuscitated structure contained logs from the actual 1809 cabin. Like Rev. Bigham, Dennett hoped to profit off of a commercialized park he called “Lincoln Spring Farm” and “Lincoln Birthplace.” When this park folded, Dennett put the cobbled cabin on traveling display. First in Nashville at the 1897 Tennessee Centennial Exposition, and later on at the 1901 Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York. In New York, the cabin was prominently positioned next to a fake Confederate President Jefferson Davis’ birth cabin. (Source: Phillipsburg Mail, October 18, 1901 (Phillipsburg, Montana).) After the last tour, the logs went into long-term storage in a mansion basement.

By 1906, the cabin still in question had changed hands to David Crear, also from New York. The Lincoln Farm Association, formed in 1904, purchased the cabin and had it shipped back to Kentucky through association memberships funds (ranging from 25 cents up) and donations. (2)

In 1909, President Theodore Roosevelt laid the cornerstone for this first Lincoln Memorial. President William H. Taft dedicated it in 1911. Ultimately, the National Park Service acquired the site in 1933 and the site remains to this day.

President Lincoln’s son Robert Todd, in 1919, wrote: “the actual cabin was a scavenged ruin long before my father’s election…the structure now enshrined a great marble building in Kentucky is a fraud when represented as the actual home.”

In 1949, after an exhaustive study and 82 page report, Benjamin H. Davis, a Historical Aide with the National Park Service, concluded: “In this case any discovery of the cabin’s ever having been associated with Lincoln would have been accidental.”

Finally in 2018, the authenticity and credibility of the Lincoln Birthplace cabin was decided. Dr. Henri Grissino-Mayer from the University of Tennessee-Knoxville’s Department of Geography used tree-ring dating (dendrochronology) to conclude the logs dated to 1861. President Lincoln was clearly living in the White House, and could never have been born in it. Regardless, this rough-hewn replica serves as a standby for visitors to gaze at and remember President Lincoln’s birthday 211 years later.

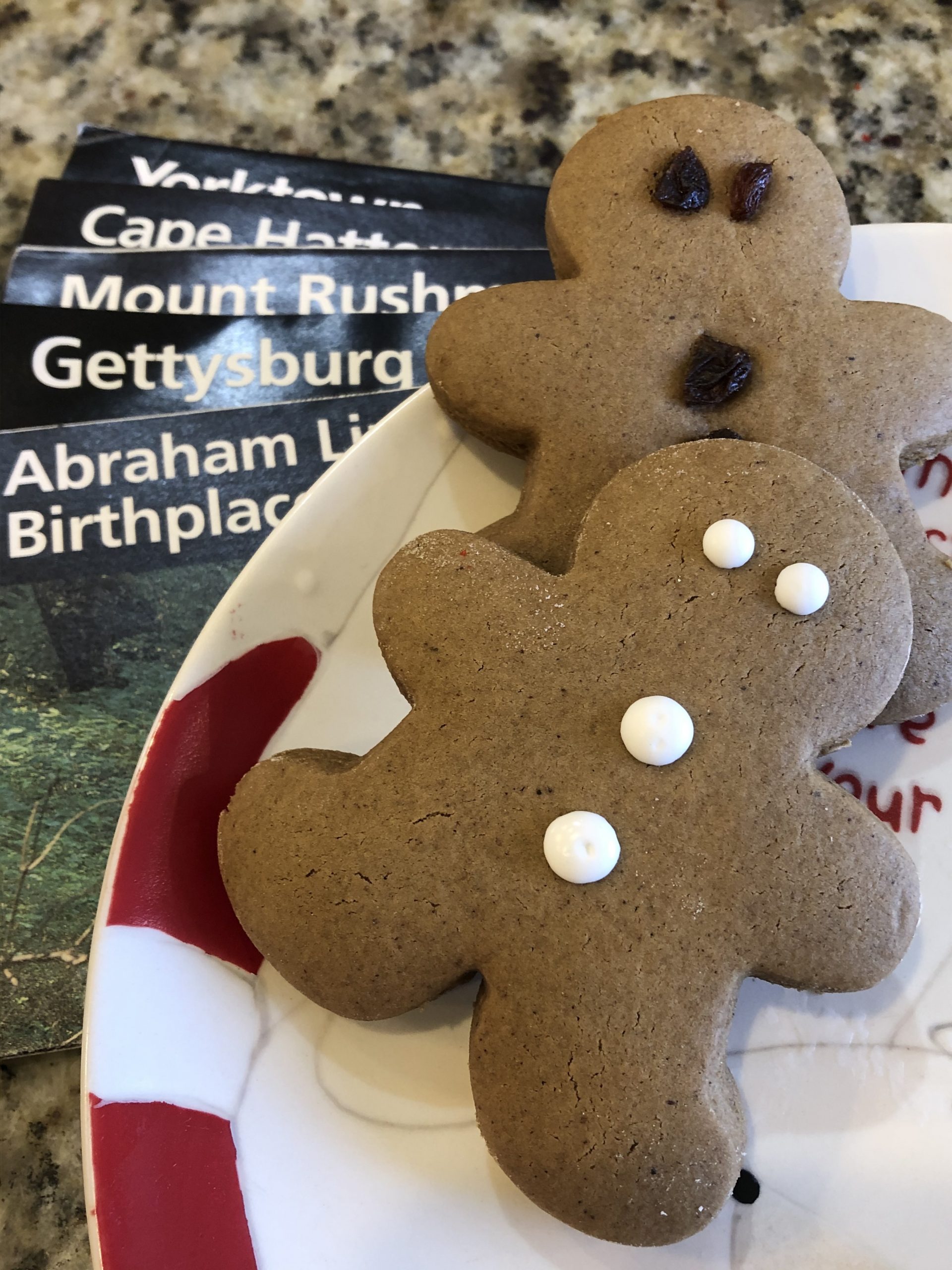

Today we’re remembering President Lincoln with Day 4’s Gingerbread Men. Gingerbread men and figures have been around since the 15th Century and Elizabeth I of England. Colonial 18th Century America ate gingerbread from recipes brought with German and Dutch immigrants. The first printed recipe for it was in Amelia Simmons’ 1796 American Cookery book. President Lincoln is reported to have thoroughly enjoyed gingerbread men as a child. His mother baked them before her death when he was nine-years-old. As a way of diffusing a tense situation during one of the seven Lincoln-Douglas Debates, Lincoln described his gingerbread experience:

“When we lived in Indiana,” the future President began, “once in a while my mother used to get some sorghum and ginger and make some gingerbread. It wasn’t often, and it was our biggest treat. One day I smelled gingerbread and came into the house to get my shear while it was hot. My mother had baked me three gingerbread men. I took them out under a hickory tree to eat them. There was a family, near us, poorer than we were, and their boy came along as I sat down. ‘Abe,’ he said, ‘gimme a man?’ I gave him one. He crammed it into his mouth in two bites and looked at me biting the legs off my first one. ‘Abe,’ he said, ‘gimme that other’n?’ I wanted it myself but I gave it to him. ‘You seem to like gingerbread.’ ‘Abe,’ he said, ‘I don’t s’pose anybody on earth likes gingerbread better’n I do–and gets less’n I do.'”

Carl Sandburg, The Prairie Years (1926)

The sorghum syrup mentioned by Lincoln is not commonly found in most grocery stores today. It can be ordered from family-run businesses like Muddy Ponds Sorghum in Tennessee. At the time of this writing, I substituted blackstrap molasses for sorghum. Blackstrap molasses has a higher sulphur content and is not as sweet as other molasses on the market.

Today’s recipe comes from The President’s Cookbook by Poppy Cannon and Patricia Brooks (1968). It features white vinegar, which is new to this baker of gingerbread cookie recipes. The result yields a play-dough consistency that’s perfect for smooth rolling, has a substantially spiced flavor, and bakes into a puffed soft cookie.

Jen over at the Presidentress blog contends that Young Abe’s gingerbread men were much differently shaped than our cookie cut-outs of today. Gingerbread men in Lincoln’s day were rolled out in snakey coils and formed into corn doll shapes (see left). Based on the scarcity of ingredients like sorghum and ginger, kitchen extravagances like cookie cutters, and Sandburg’s writing, gingerbread men in this form seems completely possible.

Feel free to roll out your gingerbread men (or women) and form them like Lincoln’s mom did. Little helper’s hands would do a great job at this! Or cut out with a cutter of your choice and decorate with raisins, icing and sprinkles.

We’re still heading west on Day 5, but staying in the kitchen’s heat is up to you. Westward ho!

PrintGingerbread Men

An old-fashioned substantially spiced cookie that’s perfectly puffed and soft! Decorate with traditional raisins or icing and sprinkles.

Adapted from Young Abe’s Gingerbread Men recipe in The Presidents’ Cookbook by Cannon and Brooks (1968).

- Author: Erin Thomas

- Prep Time: 30 Minutes

- Cook Time: 10 Minutes

- Total Time: 40 Minutes + Chill Time

- Yield: About 30, 3-inch Gingerbread Figures 1x

Ingredients

1 cup unsalted butter, at room temperature

1 cup granulated sugar

1/2 cup molasses*

1 tsp. cinnamon

1 tsp. ground ginger

1 tsp. ground nutmeg

1 tsp. ground cloves

2 large eggs, at room temperature and beaten

1 tsp. white vinegar

5 cups all-purpose flour, sifted

1 tsp. baking soda

Raisins or icing sugar for decoration

Instructions

In a medium bowl, cream the butter and sugar together until fluffy. Beat in molasses, cinnamon, ginger, nutmeg and cloves. Pour into a medium saucepan. Bring to a boil over medium heat. Allow to cool to lukewarm.

Return molasses mixture to a large bowl. Using a standing or hand-held mixer, beat in eggs and vinegar. Stir in sifted flour and baking soda until a smooth dough forms. It will have the consistency of play dough. Cover bowl with plastic wrap or a towel. Chill for several hour or overnight.

Preheat oven to 350 degrees F. Line two to three baking sheets with parchment paper, Silpat liners, or leave ungreased. Set aside.

Roll dough on a moderately floured board to about 1/4-inch thick.** Cut into desired shapes. Place shapes about 1-inch apart on prepared baking sheets. (If decorating with raisins, press raisin bits into dough for eyes, buttons or other decorative features.) Bake for approximately 10 minutes. Remove from oven and allow to cool slightly before removing to wire rack to cool completely. Decorate cooled cookies with icing and decorations as desired.

Notes

*I used blackstrap molasses, which has a stronger sulphur taste and is not as sweet as traditional, store-bought molasses. Sorghum syrup can be replaced as well. Equal amount of all will suffice for this recipe.

**To recreate the 19th Century gingerbread form, roll dough into two 1/2-inch wide coils about 4 to 6-inches long. For the body, twist a coil into a ribbon like shape. Press a second coil across the back of the ribbon shape. Bake as directed.